Bad Artist Statement #4: Dean Kissick

Dean and I talk about his recent trip to Italy, ecstatic experiences of art, the state of the novel today, and the return to trad.

Dean Kissick is a writer and Spike’s New York Editor. Dean has written for Interview, Civilization, The Drunken Canal, and The New York Times, among others. His monthly Spike column, The Downward Spiral, has over the past few years become the one thing online I consistently and compulsively read. I describe it to friends as dispatches from the centre of our hyper-accelerated present. In it, he’s chronicled the rise of NFTs, current attempts to efface the self, his summer as a meme, and, beneath it all, a yearning for a transcendent experience of art.

Dean and I spoke about his recent trip to Italy, ecstasy, the state of the novel today, and the return to trad.

Paul Dalla Rosa: Hey.

Dean Kissick: Sorry. I’m just coming back into my apartment.

PDR: Oh, OK. Do you want me to call back in like 5?

DK: No, I’m good. I’m just getting water. All right. Here we go. I’m just going to like recline on my sofa and talk to you.

PDR: Great. So, you were just in Italy. How long ago was that?

DK: That was in August. I guess just under two months ago. I went for two weeks. I flew into Rome and spent about maybe four or five nights in Rome and really hit the art tour pretty hard. I had been to Rome once, but I didn’t really know what was going on. This time I did a lot of research, so I had a plan, I mapped out where everything was that I wanted to see, and I managed to get to see quite a lot of it. Then I went to Tuscany. I went to stay with some friends in a villa for about a week and then went round Tuscany on my own.

I did the Piero della Francesca tour. I went out into the countryside and saw this della Francesca Chapel in the basilica in Arezzo. Then a couple of paintings of his in his hometown of Sansepolcro and then one painting of his, the Madonna del Parto, in the little hill town of Monterchi where his mother had been born. That was his only connection to the town. So I’d read this really great piece by Peter Schjeldahl, The New Yorker critic, that he wrote just under two years ago when he was diagnosed with cancer, which he’s since recovered from. He thought he was dying at the time. And he wrote about that. He wrote this piece about his life and art. And he also went on The New Yorker podcast and spoke at more length about this experience of going to Monterchi to see the Madonna del Parto in the 60s and how it changed his life. That’s what got him into art. And he’s written about this elsewhere, this formative experience from his life. So when I heard of that, I thought, you know, I really want to go see that painting someday. And then these last couple of years when obviously we haven’t been able to travel much at all, the place my mind kept on drifting to was Italy. I had this deep urge to go to Italy more than anywhere else, more than to go home.

PDR: Is the del Parto the one with the Madonna gesturing to her belly, and it’s almost like she’s gesturing to an opening of the immaculate conception?

DK: What do you mean by opening of the immaculate conception?

PDR: Oh, it’s like, almost a gash in her stomach. Well, maybe it’s the dress, actually, directly where the womb is, an opening as if God’s just flown in. Then there are two angels next to her parting the curtain and she’s standing in the centre in a blue gown.

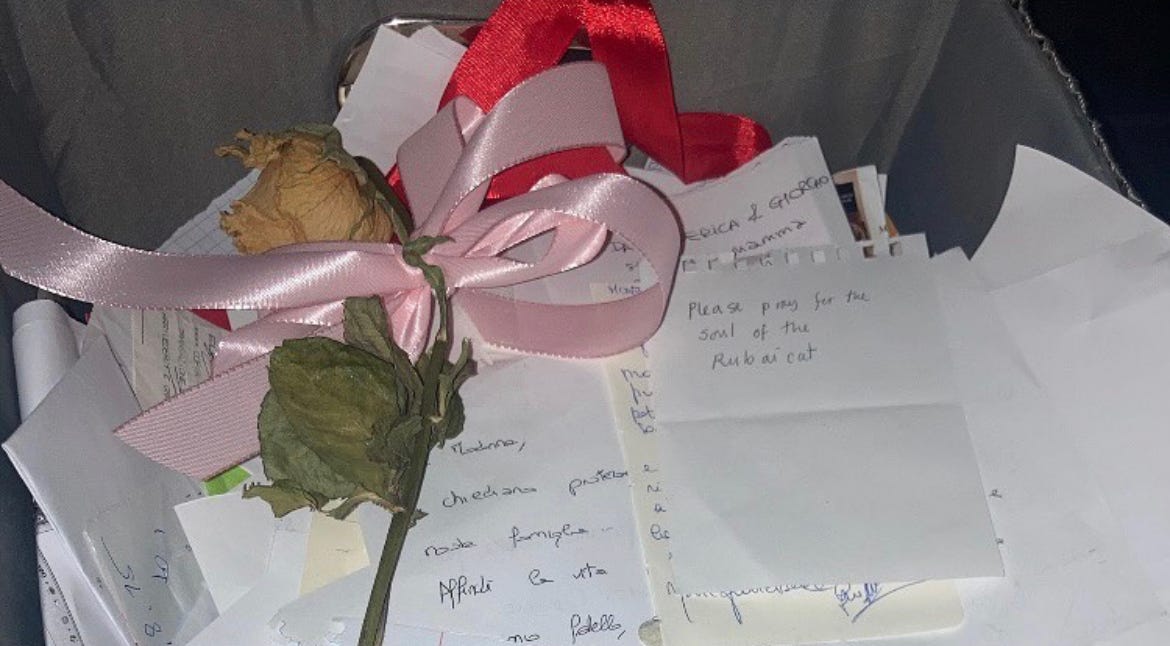

DK: Yes, she’s in a circular kind of tented structure. I think there are angels parting the curtains around her. I can’t remember offhand, I bought a poster but I haven’t put it up yet. But I know what’s going on with her, which is that she’s very pregnant and it’s a very rare depiction, particularly for the time, of the Madonna as pregnant. So it’s this great image of fertility. And he went back to his mother’s hometown to paint it. So, yeah, there’s a lot going on there. It’s quite fitting. But you could also do an interesting psychological read of what della Francesca is up to there. I mean, it seems to me like it’s a self-portrait because he’s painting a mother in his mother’s hometown who’s pregnant with Jesus. Jesus could also be a surrogate of him, and the town itself is famous for its fertility. It has a spring there in the hill that’s supposed to make the young women of Monterchi extra fertile and their milk extra nourishing. But rather than painting another trope, which would be the Madonna breastfeeding Jesus, he painted the pregnant Madonna. Now it’s been taken out of the church to a museum just to itself, and the museum just leads you into this one room where the painting is in a climate-controlled space behind glass. It’s motion-controlled so as soon as you step through the door, the lights flash on and the Madonna appears in front of you. And there’s a little tray below her where people leave letters and offerings and prayers, things like that.

PDR: That’s quite rare. I haven’t seen that before in Italy.

DK: I’ve never seen it in a museum. It’s really cool. And you can read them as well because they go back quite a bit. They don’t empty the tray that often, so you can see what people are saying to her.

PDR: Did you read any of them?

DK: I started reading one, but I felt a bit compromised. But I wrote her a letter and left it with the others.

PDR: Do you want to say what you wrote her? I feel a bit compromised asking. It feels private.

DK: No, no. I wrote for my friends. I wrote for my friends, not just myself, but my friends Ed and Alex. Friends from home, from London, and we’re all the same age and we’re all these single millennial guys. We talk in the group chat about, like, what to do with our lives, marriage and family and that sort of stuff. So I wrote, I wrote something along the lines of, that I hope we find good wives and have children. And I guess that as parents we can learn to be good fathers to those children, and that we can be forgiven for our many sins and trespasses. That’s what I wrote about. And I also wrote a little passage just asking the Madonna to look out for my young friends, Walt and Honor from the Wet Brain podcast, because you know, they’re good, young, talented God-fearing people and whenever I prayed, which wasn’t that much because I’m not really religious, but when I found myself in holy places, I did say a little prayer for Walt and Honor. Just to make sure God and Mary and the saints are looking out for those two.

PDR: That’s very beautiful. I remember being with my cousin in Milan the last time I was in Italy, she lives in Milan, and she’d taken me to the Duomo. We were inside and she lit two votive candles, one for my novel, which was very sweet, and then one for her master’s thesis. But then, as soon as she’d lit these candles and placed them down, this man, oh, I forget the name of them, the candle snuffer or acolyte, appeared with this little brass candle snuffer and snuffed them out. He just appeared out of nowhere and unlit them.

DK: Why? Why would he do that?

PDR: I don’t know if it might be something to do with the integrity of the art. Maybe they don’t want the candle smoke constantly inside the cathedral. But I do know it’s someone’s specific job to do that, to snuff them out and take them away. But it was just very funny that it happened instantly, like an Italian commedia and my cousin sort of had this look of horror on her face, and it was just so ridiculous I had to stop myself laughing. I mean you shouldn’t laugh in a cathedral, so it was very muted.

DK: Yeah, yeah that’s appalling. I’ve never seen that happen. I wouldn’t like that at all. I think things worked out for your book though and the novel? How did things work out for her thesis?

PDR: She finished it. And so that was good. So she graduated and how they do it in Italy is quite stunning. They graduate wearing laurel wreaths instead of a cap.

DK: Wow, that’s very imperial. I was just thinking about the laurels. I was thinking about Roman emperors. I was listening to an audiobook about ancient Rome while I was in Florence, and I remember hearing a story about this general [Pompey] who won all these wars, and he came back and he should have got this huge reward for this, a great day of celebration. A triumph or something like that, but I think the Senate said, we can’t let him become too powerful. So they didn’t give him his day in the sun, essentially. The highest honour you could be bestowed in Rome was when a triumphant general would return and you would be given this imperial purple cloak and your face was painted red and then you have a parade through the city. It was like the closest thing you could be to becoming a god. You almost did become a god, you know, and it must have been great to go through that. You know, to go through ancient Rome with your face painted red, and your purple cloak and everyone is out there for you. We don’t really have a contemporary equivalent to that.

PDR: No, not at all. And what other art made an impression? You mentioned buying posters. What posters did you get for your wall?

DK: Well, you know, I went to see this Pontormo. I was just posting about that coincidentally today because it turned out the new Loewe collection, which is Jonathan Anderson’s brand, part of LVMH, the new collection is inspired by this painting, Pontormo’s Deposition from the Cross. And I know this because I do a bit of branding, copywriting work for Loewe. I just found this out today. They’ve just gone back to the runway shows after about almost nearly two years off the runway. So Jonathan Anderson decided it’s time for a whole new chapter for the brand. He’s really a genius, and he did this amazing new show that’s supposed to be like starting afresh for him, for the brand, and doesn’t really have any references apart from this one Pontormo painting, which is an incredible painting regardless of all that. I went to see it. Have you seen that? It’s in Florence.

PDR: Yeah, I’ve seen it, and from memory, that’s the one that Pasolini made La Ricotta out of. I think it is. He does a recreation of it, which is quite stunning.

DK: Oh wow.

PDR: It’s incredible. But yes, that painting is beautiful.

DK: How does he recreate it?

PDR: So he recreates it on film and it’s oddly colourful for Pasolini, almost like a Fellini. It’s one scene but he stages the entire frame to mirror the painting, and from memory, uses people he just brought in from the street. It’s incredible. All of the flowing tunics and cloaks in really vivid pastels and then Christ being brought down from the cross. It’s just a short film. But it is, yeah, pretty much an almost direct reproduction.

DK: Oh, I need to see that. I need to see that. I went to see the painting first in 2017. I was in Venice for the Biennale and I went to the opening week and after that I went down through Italy on my own. That was the first time I’ve been to Florence in my life. It really blew my mind when I first arrived in Florence. I just didn’t know it would be like how it is. And so I tried to go see the Pontormo that year, but at that time it was being restored or maybe had just been restored and moved out of the church. So I got to go back four years later this year and finally see it. And it was, yeah, it was amazing. It was worth it. It’s one of those ones where it’s in the dark, gloomy church and you drop a euro in to light it. It’s been restored for the colours. It’s incredibly bright, kind of garish, right now. So when I first saw it flash up in front of me; it was what I wanted, what I’d been looking for. That and the pregnant Madonna really affected me. And all this stuff in Rome. I had seen hardly any Caravaggios in my life before, and now, in five days in Rome, I saw so many Caravaggios, like an excessive amount. And I’ve never seen Bernini. I got very into Bernini, you know, and learnt about him, and I’d never seen these Borromini churches either. There’s two in particular that are just mind-blowing. I think seeing all that completely blew my mind. Then there’s that bridge into the Vatican City, the bridge over the river.

PDR: Yes.

DK: And it’s lined with the angels. They’re copies of the angels, the big stone copies of Bernini’s angels, that is. It was just incredible, that experience of walking over that bridge in the sunshine. That was really quite something. The whole idea of the Vatican is quite something.

PDR: I do love the Vatican. I think entering St. Peter’s is sort of that. I don’t know. It feels like you’re entering another state like it’s outside of the world, something eternal, almost coming into heaven.

DK: I mean, yeah, it’s amazing. I’d like to go live there for a while. Go hang out in the Vatican. I’m told it’s not possible, but if anyone knows a way, I’d love to go do a couple of months living in the Vatican City. One of my favourite things at the Vatican Museum is just having these vantages where you can gaze over into the gardens and the weird buildings, the weird parts of the city that are completely blocked off. And who knows what’s happening in them? You know, I have no idea what is going on in that place. That’s what I really, really want to go see.

PDR: Did you do the Pope’s mass or anything like that? I don’t know if they’re doing them at the moment.

DK: No, I didn’t, but they’re doing them. They’re doing the Pope. The Pope doesn’t stop, you know, unlike a lot of these secular organisations, say, that that have taken the last couple of years off to not do anything and stop catering for their public. The Pope has been keeping on going, keeping on seeing his people very regularly.

PDR: It’s admirable. And surrounded with all of this art, did you feel yourself having an ecstatic experience with anything? Or were you overwhelmed with a sense of profundity?

DK: I definitely had a sense of profundity. I didn’t have an ecstatic experience. I think I had many small, ecstatic experiences, many small epiphanies or these small moments of great beauty. But I was never overwhelmed, never brought to my knees, which is a great shame because I would have liked to have been. I was trying to force it in a way. I was seeing a lot of art in a short period of time and really rushing over the city in the August heat, staying very caffeinated by drinking a lot of great cappuccinos and having a lot of pastries and stuff, and I think that’s the way to do it.

I quite like the intense marathon approach to viewing art, which is what it’s like to go to a big biennial, to go to Venice or documenta or, like, run around Rome, that feeling when there’s too much to see, but you’re trying to see what you can and you’re running around. It’s often at the end of the day when I’m really tired or worn out or hungover and subsisting on coffee that’s when, if I can see something really good, surprising, in that state, that’s when it can really pull me out of the world, really step up and grab me.

PDR: I think that’s true. I find when I’m reading hungover or somehow emotionally disturbed, that’s when I’m most likely to have an ecstatic experience or an approximation of it. Your defences are lower, maybe. I often think about the opening of Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station, which opens with the narrator viewing van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross. But he sees this man in the museum standing in front of the painting burst into tears. And the narrator’s only thought is one of anxiety because he doesn’t think he’s ever had a profound experience of art. And then he’s worried that if he has, it’s only been a performance. And I think that’s related to why I like The Downward Spiral so much because I feel like your column involves the possibility of a profound experience of art, not that every column necessarily describes one.

DK: Oh yeah, I’m very glad to hear you say that. I mean, I definitely believe in the profound experience of art, and it’s happened to me a lot, and it happened to me in Italy many times, certainly. But unfortunately, I didn’t get the full Stendhalian breakdown, right? I didn’t faint or hallucinate or anything like that, although I would have liked to. Ben Lerner is one of my favourite novelists, contemporary novelists, for sure. I think he’s so good. But there’s also something very disappointing for me, or it’s very representative of our moment that one of our great writers’ breakthrough novel begins with this complete denial of the possibility of transcendental experience. The work of art and then so much of fiction is so realist now. It’s so self-reflexive. It’s modest in its ambitions or polite in its voice and its scope. We’ve lost a lot of that transcendental ambition or magical urge, of trying to depict or suggest utopias or some grand vision or some otherworldly experience.

PDR: I do agree with that. My [possibly abandoned] dissertation is actually on Ben Lerner, which I feel like everyone’s dissertation is on Ben Lerner. I mean, it’s not just on him but he’s one of the main ones. But I do think that’s true what you’re saying, and I think there’s a limitation at the moment where people just want to represent what’s going on with them, internally, which I guess is sort of the novel. But there is a limitation that people don’t want to reach for something more. I find it quite sad that the systems novel doesn’t really exist now, whereas you know, DeLillo or Pynchon or all of these people would try and make a grand statement or try and reach towards that. That’s just one example. But no one seems to really want to do that now. And, you know, I’m probably included in that.

DK: What was your approach to Ben Lerner?

PDR: It was looking at autofiction but trying to use a lot of French autofiction theory from decades ago. I suppose what I argue is that autofiction is less of a new development and is more so writers trying to reach back to what was initially exciting about the novel, which was a closer way of depicting reality. So it looks at a lot of specific things that novels are doing now, like Ben Lerner breaking down barriers between himself and the narrator, in a way that might make the reader think that they’re one and the same. But that is something similar to what writers have been doing in the novel anyway for 300 years. It’s just, yeah, a return to that, I think.

DK: It’s autofiction all the way down?

PDR: To an extent. Have you ever read or seen Franco Moretti’s The Novel?

DK: No.

PDR: So it’s this huge theoretical work which you can only actually read as two volumes, and it’s a collection of writings on the novel. But there’s a great essay, Catherine Gallagher’s “The Rise of Fictionality”, in which she references, I’m paraphrasing, that the novel and our understanding of fiction appeared at the same time 300 years ago. I mean, it’s more complicated than this, but she references this argument that back then a lot of French writers were doing what she terms “libelous allegory”. But what that led to was this explosion of litigation. So then the argument that came through to avoid prosecution was, no, this allegory isn’t real, this is all fiction. And then that, in part, kind of set us up with an understanding of fiction, which we use today. This is quite recent. When you go back, you know, to the epics or the Roman works, there wasn’t a clear distinction between what we would think of as non-fiction or fiction.

DK: Yeah. Maybe those boundaries have broken down again. There’s definitely a lot of space for, you know, first-person voice in magazine writing and that kind of thing now, which really wasn’t the case that long ago, anyway.

PDR: I’ve heard you’re working on a novel.

DK: Well, I’m always working on a novel but there’s nothing to show for it. But that’s what I’m always doing, and that’s still the highest form for me. That’s what I’d like to do with my life, like, write a good novel. That’s what I’m most interested in seeing from other people. That’s what I want to see in the culture, just more great novels.

PDR: How long have you been working on it or has it always been a series of novels?

DK: The main thing I’ve been spending my time on is writing various failed novel projects for probably five or six years now. The most recent one, I’m pretty sure I started this year. But you know, I think this one’s going somewhere, I feel like it. I’m enjoying the process. I feel like it’s not a waste of time. I think it’s getting somewhere [it’s since been put on hiatus].

PDR: I think that’s the most exciting part. I think there’s this period when you’re working on something and it’s just you with the thing. Every morning, even if I have work at 9 or something like that, I’ll make a coffee at 7 and then just sit in my little courtyard and write and that’s the happiest time for me. And then when you start having to put everything together or thinking about selling it, that’s where it all goes to shit.

DK: Yeah. I also like to have a coffee first thing, no breakfast, and sit down outside with a pen and paper. When the weather is good enough to write in my notebook, that is also the happiest time for me. Nothing can really beat that feeling when you’re lucid, you feel good, ideas are flowing. It’s a beautiful thing. Recently, actually, I’ve been going to the gym first thing and then having a coffee and writing after that. That’s pretty good as well. That can put you in a weird state of euphoria.

PDR: The endorphin rush.

DK: Yeah. So when I was in Italy, I was cutting up these art visits by trying to find nice cafes where I could sit outside and drink a cappuccino and write in my notebook. I was doing like a constant flow of that through the day, and then maybe some writing with wine at a restaurant or wherever in the evenings. It’s a really incredible way of life. I think it’s the best way of life.

PDR: I have a failed novel that I wrote the bulk of while I was living in Giancarlo DiTrapano’s apartment in Rome for about a month. I’m so grateful to Gian and his husband Giuseppe’s hospitality because it’s something I’ll never forget. I spent every day of it living that life. Every morning I would go to the Borghese Gardens and just lie down and write, and then I would go to a bar or a cafe. And that was, yeah, looking back, probably the peak experience of my life—this time of idyll.

DK: In the Borghese Gardens every day. That sounds incredible. And so what happened with your novel? The one that a candle was lit for? Did it not turn out well?

PDR: Urghh.

DK: You sound so pained.

PDR: No, it’s not painful. It was this autofiction novel based in Rome and a lot of my time in Italy and about the desire to make art or rediscovering that desire. And I was working on it while I was writing my story collection, so I was working on it for four years, but then for some reason, I feel like that moment... it’s not that the moment’s passed, it’s just not the thing that excites me anymore. And it was funny. I made a big thing with my agent that I didn’t want a two-book deal even though I had this almost finished second manuscript. Maybe that was a mistake. But I just didn’t believe in it anymore. I’m more excited for what’s next.

DK: Hmm. Well, I think you’re right that you can’t publish the novel if it’s not what you’re excited about. You know, you’ve got to come out strong.

PDR: Yeah, completely. There’s no point in doing it otherwise. I was going to ask about, I suppose, in Italy there’s so much religious work and I guess something you’ve written a lot about is a sort of return to tradition that’s happening at the moment or is in the periphery. I wanted to ask about that. What do you think about the return to religion or the return to trad?

DK: I’m not religious, but I was raised in a religious environment, but growing up in England, everything’s religious, but kind of nothing is religious. You know what I mean?

PDR: Yeah. Was that Protestant or Catholic?

DK: Protestant [having looked this up, it’s neither]. I went to a Church of England School. I went to a religious high school, we’d sing hymns every day and say prayers, but it just felt like no one believed in it all. It’s all just something you do there. So the return to tradition... I’m definitely open to it. And I’m definitely in my grumpy old man phase and I’m enjoying that. I studied history of art so I’ve always liked some old stuff, that’s what really gets me excited, like Renaissance Italy, but particularly early 20th-century France, 19th-, 20th-century art, the dawn of modernity. I would have loved to have been alive in those times. There is a sense of cultural exhaustion right now, which is something that maybe I’ll ask you about at the very end.

But you know, I just went on my trad pilgrimage to Italy, my first trip out after this long period of stasis and it was brilliant. I’d recommend it to anyone. I think there’s an association of the return to tradition with being reactionary, and understandably so because it is a kind of reactionary impulse. And so you have, you know, all of these traditional architecture accounts on Twitter and some of them have this explicit reactionary political agenda.

But at the same time, it’s kind of hard to disagree, you know, when they’re posting these pictures of old cities and saying how beautiful they are. It’s hard to walk around Florence or Rome, the Borromini twisting spire or the church with the four fountains on the corners and not think this is beautiful. Something I’ll often think is that you’ll have a traditional architecture account and they post, maybe some, say, 17th-century Flemish architecture or something as a sign of beauty, and then right next to it, in the same tweet they’ll post some 70s brutalist concrete building and say, “How hideous is this?” But you know, I think both of those things are incredibly beautiful. But the problem is, what’s happening now. The problem is the kind of the culture we’re producing now.

One thing I’d say is it really strikes you—actually, I’ve heard that Sally Rooney says this in her new book as well, but I haven’t managed to get a pdf of that yet—but it is kind of striking to be somewhere where all these incredibly beautiful things were made five hundred or more years ago. And to know that we couldn’t, we literally wouldn’t be capable of doing that now. Like, there’s no one on Earth who could make that painting. There’s no one who can make that building. Aside from the fact that no one’s even trying to do it, you know. That’s humbling, but it’s also puzzling to me that we can no longer create such beauty. And it’s puzzling to me that we no longer try. There’s not a single city in the world trying to create such a beautiful architectural neighbourhood or anything anymore. And I don’t understand why that is.

We seem to have turned against beauty in a way. Like here in New York we have Thomas Heatherwick’s Vessel, the much-maligned Vessel that keeps getting closed because people are killing themselves on it. And you know, I actually think it’s quite beautiful and it’s something new. In the flesh, it looks pretty stunning to me. But aside from the fact that it drives people to suicide, it’s not finished. If you look really closely at the details, it’s kind of fucked up. It’s like we no longer have the capabilities of building things up to a perfect finish.

PDR: Yeah, I’ve seen the Vessel but I haven’t seen it up close. I had a strange experience there. My partner really wanted to see it, and we sort of came out of the subway, I don’t know if it’s the Hudson Yards or whatever the subway stop is, but we were approaching it, it was in my field of vision, and I was overwhelmed by a migraine. I probably haven’t had one like it since I was maybe 12, where I’d get the aura and everything, then start vomiting, every neuron just screaming. So I actually couldn’t even approach it, at a certain point I couldn’t stand. I don’t actually know if it had anything to do with the Vessel but it ended with my partner having to spirit me away in an Uber and me blacking out.

DK: But it might be connected. It could be. It has a weird effect on people. I think it looks good, but I’d like to go up it when it’s next open, really see it up close.

The question of returning to tradition, I think there are various kinds of reasons for doing that, but returning to tradition doesn’t necessitate going back to an old way of life. It can also just be a way of finding alternatives in the present or different ways forward for art, writing, design, how you live, you know, all sorts of things.

Something I was talking about today was the Loewe show, as it feels like Jonathan and his team, they wanted to start afresh with this very contemporary fashion brand. So they went back to Pontormo and then took this Pontormo attitude, this mannerist, iconoclastic attitude and just went into the studio without references and experimented and built an all-new collection. Trying to build a new aesthetic out of this five hundred-year-old painting approach.

This is what Leave Society is about in large part. Tao Lin’s gone a long way back, you know, he’s going many thousands of years back in order to find what he considers better ways of living. He’s going so far back that it’s going beyond the reactionary conservative values or traditional ideas of beauty to this ancient matriarchal, utopian pacifist society that may not even have ever existed. But that’s what he’s finding, like deep, deep tradition. And with some of my favourite painters, say, Julien Nguyen often looks at the Renaissance, but twists it into something new. My friend Damon Sfetsios is really obsessed with going out into the fields and trying to learn to paint like Cézanne.

I think throughout culture, it seems to me that we have a real dearth of new ideas. And one way many people are looking for new ideas, or at least very, very old ideas, is just to go way back and then try to do something new with that. I went to the opening of the New Museum Triennial yesterday, a contemporary art triennial here at the New Museum on the Bowery. And the show was fine, but it was so flat. So many big contemporary art shows are like that now, especially the biennials, the big exhibitions. There’s nothing really good. There’s nothing really bad. There’s nothing subversive or provocative. There’s nothing overtly political. It’s just all this very flat art, some of which is perfectly nice, or clever, but I find myself walking around them despairing because it feels like there are no new ideas in art, and so much of the stuff that’s being shown here that’s meant to be the cutting edge, could have been made 10, 20, 40, 80, 90 years ago. That’s weird to me. But in that show, there’s one artist, Kate Cooper, who is making this really weird CGI film of things pulsing in and out of someone’s body, and that felt new, the only new thing in there. There was also an Argentinian artist called Gabriel Chaile and he made this giant matriarchal clay mother sculpture, maybe 20 feet high, out of clay embedded with eggs, real eggs. It was inspired by some Mesoamerican pottery culture dating back to 400 BC and that was also very good. You know, it’s funny that contemporary artists are coming to New York and building these like two-thousand-five-hundred-year-old clay forms and that feels more fresh than almost anything else there. But that’s the weird situation we’ve found ourselves in.

What do you think? I’d have two questions: One would be what do you think about the return to tradition? It’s a big question. And also if you agree or disagree that culture seems to have had a sort of exhaustion point in the last few years.

PDR: Yeah, I think partially it might have to do with that. We’re in this sort of prison of the present at the moment, which is completely ahistorical. I notice it all the time, really, whether that’s writing online or Twitter or criticism or novels or documentaries, whatever, where there seems to be a disconnect from the past. And no one can really link the past to the present or what I notice people often do now is project the present into the past, a revisionist impulse which is fundamentally flawed. That in itself to me seems like an attempt to escape the past but I don’t think ultimately you can escape it. It returns. And I think that a part of this sort of return to tradition or moving back to prior forms is almost people rediscovering something other than the now. I find Leave Society very exciting and interesting, partially due to this. I mean the whole book is about a sense of discovery and curiosity and, ultimately, hope.

I admittedly don’t really love reading contemporary novels. I find they’re very sort of beige and boring, but I do like reading philosophers who look at the present. I really love Franco “Bifo” Berardi and Byung-Chul Han. I think they’re very good at describing the moment we’re in. Byung-Chul Han’s Disappearance of Ritual in particular, because it seems like our society has lost all of its sense of ritual and has sort of divorced itself from these ways of living that seem to be central to being human. In the absence of these shared rituals, what we have is individualism and semiocapitalism, which I do believe have a sort of suicidal impulse beneath them, you know, something which is very anti-life. I mean, you see it now. All we do is mediate ourselves and what ends up happening is we sort of drown in the self.

I do think that the return to tradition or things like that is an attempt to escape that and sometimes that does become reactionary and overly identarian, which is a trap, of course, but everyone’s turning identarian. These are broader problems. Everyone’s sort of lost out there and partially where I think that’s coming from is that everything is sort of a simulacrum now and people, government, brands, whoever, can say one thing but mean something else. So everywhere is just this revolving display of mirrors and I think that that’s sort of fracturing people’s psyches. I really do believe that the return to tradition, sort of reaching back, is an attempt to, I don’t know, recreate oneself as a human or to try and make something new, if that makes sense.

DK: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. My friend Paul will always say that reality ended at some point in the 60s. And ever since then, we’ve been in this sea of signs, mirrors and simulacra. So in that sense, it makes sense to go back before, if you’re trying to return to something real.

PDR: Completely but then you can’t quite return either. You’d just make another simulacrum. In terms of exhaustion, what you said before, I think you’re right. I think we are stuck in this sort of end point and can’t articulate something to get us out of it, the only thing we can do is produce more, overproduce everything, which is something you mention in the column. I think we all, well I know I do, suffer from information fatigue syndrome or a fatigue of everything. It makes me think of Bifo’s And: Phenomenology of the End, where he has this really incredible conclusion where he describes our civilisation as dying or going through an apocalypse but what he argues is that what we have to do now is somehow not just look backwards, but accept that the reality has changed and to somehow come out of it as something new. At some point, we need to make a leap. We just don’t know what that leap is yet. But I do think that the most exciting new art is attempting to make that leap, and maybe it lands in the wrong place but there’s something exciting and wonderful about that.

It’s funny. I can say all of these things, but then, you know, if I look at my own work, I’m like, is that what I’m doing? I feel like I’m always trying to represent the present, but maybe we have to do more than just represent the present and create something new.

*