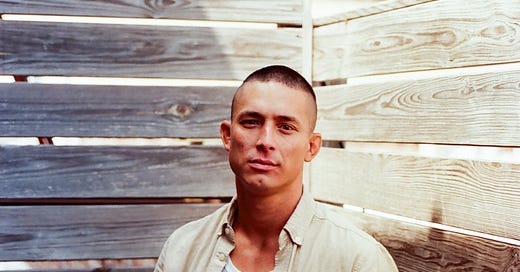

Bad Artist Statement #9: Sean Thor Conroe

Sean and I talk about immediacy, Lish-ed out energy, autofiction and getting to the real thing in art.

Sean Thor Conroe is the author of Fuccboi: A Novel. I remember hearing of Sean in WhatsApp and Instagram messages from Giancarlo DiTrapano, the founder of Tyrant Books and Fuccboi's initial editor. Gian was saying how great it was going to be, how tight it was. Gian's a good hype man to have. He didn't lie. The novel's about living today, being a man today and sometimes fucking it up. It's thrilling to read for the same reason that usually makes me thrilled to read something. It's an expression of the present.

Sean and I got together in Brooklyn, sat outside on the street, and spoke about immediacy, SoundCloud rap, Gordon Lish, autofiction and getting to the real thing in art.

Our full conversation is being released simultaneously on Sean's podcast 1storypod.

Paul Dalla Rosa: I don't think I know how this will work. This street is pretty loud.

Sean Thor Conroe: Yeah.

PDR: I think it's fine. I can see the recording bars.

STC: I have a voice recorder, too, if you want me to start recording.

PDR: Yeah, if you want to record. Just in case.

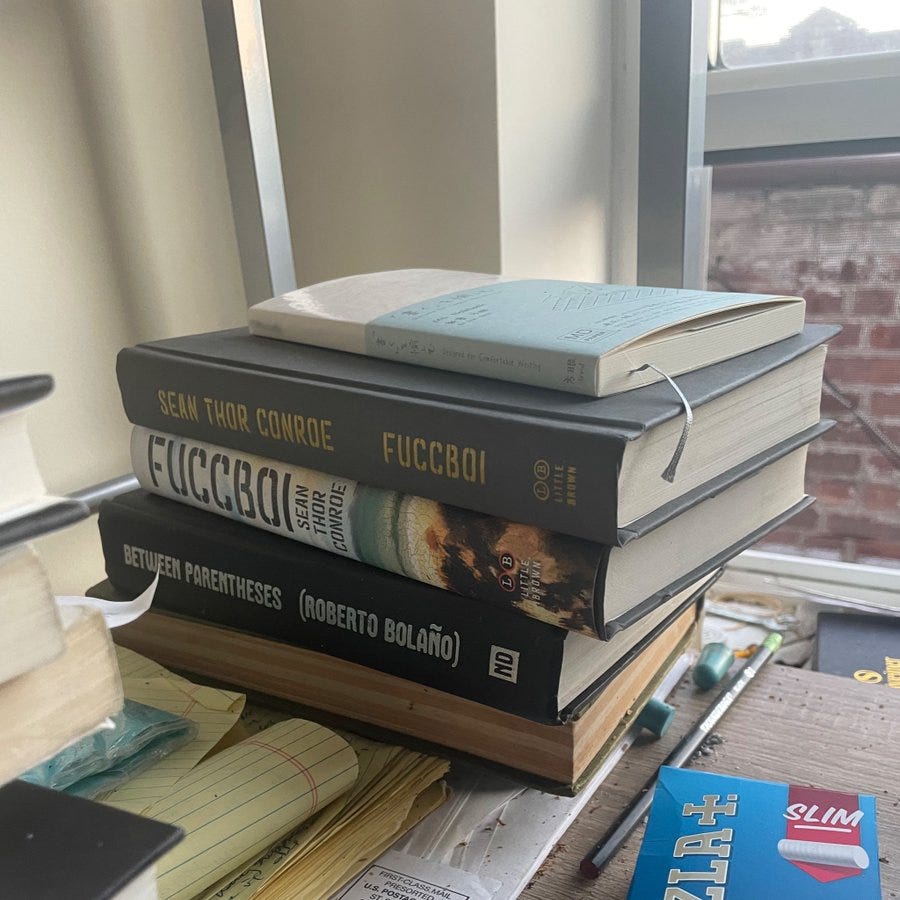

STC: Have you ever seen that Biden meme? The Hunter Biden one where he's got the million things around him? That's like me every time I'm about to do a podcast, like I put up seven recorders. Anyway, what I was just saying. What am I reading? I've been reading longer stuff that I just wanted to read for reading's sake. And then I've finally been actively writing, so I'm only reading things that are syntactically impressive, you know. Something exciting enough that I just dip my head into the story, and then it makes me want to start writing.

PDR: Yeah, I get that. It's like I've got enough time to read, but I'm not going to read something unless it's doing something exciting or interesting.

STC: Definitely. I was reading like really old, old ass French novels that are completely outside of what I do. I was like could I do this? Could I do, like, a roaming omniscient narrator? And, like, what was going on in France in the 1800s? Now I'm just reading stories that in some way have interesting stuff going on.

PDR: Yeah.

STC: Basically, I'm just going back to reading the Tyrant voice.

PDR: That's all great stuff to read. And yeah, I'm really excited you wanted to hang out. I really love Fuccboi. I reread it yesterday on the Amtrak.

STC: That's terrifying.

PDR: No, I really love it. I remember when it came out it had this big moment in Melbourne, well, it had a big moment everywhere, but everyone was talking about Fuccboi. I'd be in these situations where it would come up again and again. I remember I interviewed Marlowe Granados for Bad Artist Statements and it came up. And then weirdly, that interview finished at maybe like eleven, and I went straight to a party and then as soon as I arrived, someone was holding your book.

STC: Oh, man.

PDR: Yeah, it was funny. And I was like, this guy was holding it, and I was like, "Oh, you know, what do you think of it?" And he was like, "Oh, I love it. Everyone's just been passing this one copy around my law firm."

STC: Like, some law firm, bro?

PDR: Yeah, it was really sweet. And then, later, I had a separate friend that was texting me photos of the book, like passages they were laughing at. I remember people debating if the book was more for men or women.

STC: That's crazy. I don't know if women or men like it more or if it's more geared either way.

PDR: I think anyone could read it.

STC: Yeah. I feel like some dudes get weirdly mad about it or something. Like guys in a workshop, you know, being like, "How can you write like this? How can you talk like this? If I can't talk like this, no one can." You know what I mean. Like, "Why is he allowed to do this?"

PDR: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I get it.

STC: I think there's similarities in what we're both doing, though; How we're both immediately going into intimate stuff, having a narrator who's toggling between that and work. Then also some parts about writing stuff, like the narrator in your story that's trying to write.

PDR: I think it's like what Sean says in Fuccboi when he's listening to and talking about SoundCloud rappers, like Lil B, XXXTENTACION, Ski Mask, how someone can do a one-minute song that launches straight into the verse. There's no fucking around. You're straight in it, and that's true for the entirety of Fuccboi.

STC: Yeah and I think syntactically, in your work, you do that even clearer, like with how every sentence starts. I remember when I was talking to Gian about Scott McClanahan's book; about his experience editing Scott's book. They would get into these huge fights, where Gian would be like, "You can't start every sentence, every paragraph with like, and so then." You know, cause Scott's always just like telling a story. And I feel like I have some of that, too. I mean, I like to get an entry point of some kind to indicate orality, but sometimes when stuff's even more pared down, like your stuff or Garielle Lutz's, I'm like, oh yeah, you can even go right into things, you know?

PDR: Well, I'm like doing something reverse on this new book. So, we'll see. But it was like, I just spent like five weeks in the woods with it on this residency, and all I could do was write this really interior kind of crap, and that stuff was good but I just couldn't get it to move. And then reading Fuccboi on the Amtrak, I was like, yes. This is what I need.

STC: Right, right, right. Declarative verbs of actions.

PDR: Yeah.

STC: I definitely think go right into it. Sometimes I look at like how pared down Fuccboi is and how much it's like "you're going to listen to this story." It's kind of like first book desperate, you know? Whereas now I'm like, there are parts when I'm writing like trying to establish authority by being like, I'm doing what I'm going to do now. You know? And that's important, too.

PDR: Yeah.

STC: But yeah, the first ninety of Fuccboi is like, "You're gonna read this. I'm not letting you go." Maybe it's a good urgent energy to have.

PDR: Definitely. What I really like about Fuccboi is what you're doing syntactically on the level of the sentence, and that's actually what propels someone read it. Sometimes I get the impression that some people just opened a copy of your book, looked at like one thing, the diction of the narrator maybe, and was like, I don't care about this subject matter, so, therefore, whatever, it's all bullshit. It isn't sophisticated.

STC: Right.

PDR: But, like, syntactically, its flow is pretty incredible. Like that movement doesn't come automatically. It's constructed.

STC: Definitely. It's funny. I don't know. It's like as soon as you say one word that indicates the narrator's like a dumb bro, immediately there's no... I don't know. I wonder if people who talk like that are even reading the book.

PDR: It's a good question.

STC: Although the thing is, when you are syntactically like—well you do this too obviously—where you're just like turning the sentences, going into a rhythm, going against a previously established expectation or flow. If you're doing it right, you don't feel like it's happening as a reader. And so, you're like that was too easy to read; this must have no rigour. But it's like the fact that it was easy to read is the point.

PDR: Yeah, I think what you said is right. When something's easy to read, which is more about flow, people can mistake it for being simple or artless because they're moving in the current. And that impression's even more intense when a book subverts the expectation of what people think a literary book should be. Like what's a literary book? To me it's something that should be alive.

STC: That's some Gian shit right there.

PDR: Yeah. I'm interested in what you're thinking about when you're working on sentences. Like, what level are you writing on?

STC: So, first, it's getting a rip down. Initially by hand. And then, I've said this before in interviews, like entering it into Notes app and then having this morning ritual of playing Tetris. I'm like tetrising stacks around, you know, so the flow never breaks. Like keeping a bubble fucking not popping or something.

PDR: Keeping it taut.

STC: Keeping it taut. There's obviously people like Lutz or Lipsyte or Ben Marcus or any of the Gordon Lish people, where there's syntactic stuff I'm aware of, but it's simultaneously titrating that stuff with, I hate saying high, low, but just like the perception of what kind of guy the narrator is. You know, from a class level or something, though it's not so deliberate, I would say. But then also in some chapters, like having questions, like live questions about the ideological implications of what you're saying and constantly titrating that too. So never sitting still. Then I get like a giddy feeling when all those things are charged up. You feel it.

PDR: Yeah, the intuition kicks in.

STC: I've read Lish people, but like, I don't know all the terms and stuff. I think about this writing raps too. I sometimes think that where you're kind of operating on some like Lished-out energy of like repeating stuff or breaking the rhyme and stuff, but I don't have the terminology. It's definitely more intuitive how I think of it.

PDR: Yeah.

STC: And then, you know, I see it in your prose too, like places where you're doing repetitions. And I would say there's that kind of like Lish-type syntactical awareness, but then equally the attention to the orality of it. Because sometimes there's like a super syntactically complex bar I'll read in someone's work, but, at the same time, I don't know if it would hit for someone else to read it out loud, you know? But repetitions sometimes reflect speech more. And a lot of those stories like Richard Ford, like Barry Hannah, they're very oral too. Even despite how complex they are.

PDR: I wonder if part of that's coming from the structure of the Lish workshops, in which you know you have to read the story aloud. You have to keep Lish listening.

STC: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Exactly.

PDR: And if the piece paused or a line didn't hit, he would just be like, next.

STC: Exactly, exactly. Yeah. Like sometimes going short, sometimes going long. I don't know. I say it is intuitive. How do you think of it?

PDR: Yeah, it's funny. I'm always trying to work at the level of the sentence, but I'm not really thinking about terminology either. I'm not thinking consecution and swerve. I'm writing about, you know, to me, a sentence has to be balanced, or it has to do something. It's like, I can sense that when I'm reading it. I can't always say what's not working or why it's working, but I can feel the rhythm. That's why something that I find really hard is when I have to make a repeated change in something. There was an instance with the collection when the copy edits came back, and I realized two characters had the same name and they were in consecutive stories. And I was like, I can't have that, but changing it to a different name just fucked everything because I'd been writing to that syntax.

STC: Interesting.

PDR: So I had to pick a name that was, like, close enough on the syllable level so that it wouldn't drag everything too much.

STC: That's interesting. Yeah, I've got some name stories I'm working on. I had this exact same thing where it was like, will it be a biblical name, and thinking, you know, what's more important, like the significance of the name or the syntactic quality of repeating it throughout? I think I want to go for syntactic quality, but with the secret biblical meaning.

PDR: Yeah, they can come together. But, like before, I do think about orality a lot. I can't actually work in the same room as my husband. I mean, it's not that I can't write when he's around, but he gets annoyed cause when I'm writing, I'm like muttering because I'm reading aloud the sentence I'm working on again and again to try and feel it.

STC: Nice.

PDR: I'm interested in something with Fuccboi. Do you want the character to change in Fuccboi or the book to change the reader? Or do you want both?

STC: I don't know if this is how you're asking it, but one of the things that took so long to finish the book was this idea of if the character should change. There's like different endings where in one he just starts like wilding out again, you know, that was the end. Like, no one ever changes. And the other one, he meets his ex and they make up and he's like, "I'm a good guy now." That sucked too. It felt like it was just like, he needs to start working. I did an interview the other day and this came up, or it comes up a bit, like people telling me they haven't been able to stop thinking about it. And I think that that's the power of authority that comes with doing declaratives. Almost like having some animosity towards the reader. Like that's just Houellebecq, like comes from me reading a lot of Houellebecq who likes having a narrator who has a world view at times and just says stuff where you're like, "No." But then like, why are you still reading?

PDR: Yeah. A complication.

STC: I think I usually maybe write the character kind of static, but then I feel like I have to be changing when I'm writing it. You know what I mean? Like, something in actual life has to be confronting and confusing me. And then, like I'm trying to work it out or like playing with it; trying to see different sides.

PDR: That's vital. I get that. I'm teaching a class when I'm back in Melbourne, and it's like that's always the hardest thing I find to teach. Like someone can write a nice short story, you know, technically proficient, but it isn't alive. What I try and teach is like whatever you're writing has to be really important to you. It's not just this abstract, "Oh, I want to be a writer, so I have to tell a story." It's like, no, this story has to be really close to your entire being. If it's not at that level, why should the reader care? Why do you?

STC: Yeah. It has to be, like, directly connected to your life, you know? It was interesting, like I was talking to Tao a little bit about that when I talked to Tao last week. Even though we do it in different ways because I don't feel like when I write autobiographically, I'm like... For example, writing about a parent. I feel when Tao's writing, he wants to write and depict his mom in an accurate and complex way. Whereas I guess I am too kind of in some ways, but like, I feel I'm way more aware of what I need the story to be. Like, in Fuccboi, it's about this kid. This character is a boy. He's a boy and this is his mom. I'm thinking about it like that, you know. But I think how we're connected is like how Tao says he writes stuff that's literally helpful to him in his life. I think I have that same energy, too, even if I do it differently. I think a lot of people don't have that. And then like, you start reading a story, and it's like, this is completely dead. You know what I mean?

PDR: Completely.

STC: And then in person the writer will start telling you something about their life. And it's like, why aren't you writing that?

PDR: You said a line in your Contain episode, Nietzsche Was Like The First Rapper, I really liked. I wrote it down. You're talking about writing and about asking yourself "How is this book helping you understand how you are actually living?"

STC: Yeah.

PDR: I think that's the key. That's how you do it. I do kind of think that like everything you write is going to be autobiographical in a way; even if the events are wildly different, even if a character is different, it still has to be talking to your life in some way. Or maybe it's about needing to try to figure out something external to you, but you grapple with it internally just in the act of writing it. With the collection, each story was me trying to figure out some emotional problem.

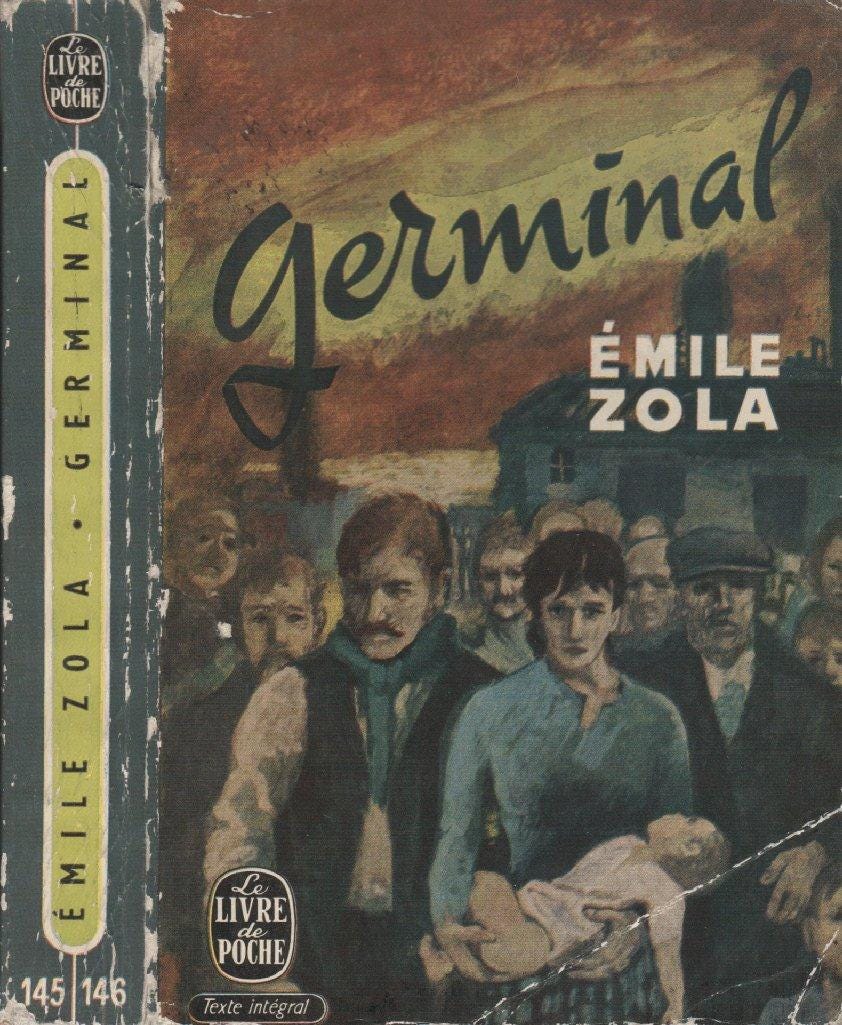

STC: And I felt that immediately. And that's why I was fucking in. You know, I mean, even old ass novels like, I just read this book, Germinal by Émile Zola. And the main character is this dude who, like, pulls up to a mining village, starts being like this is fucked up, we're not getting like enough fucking shekels, you know, and rallies everyone to do a strike. He starts doing speeches to everyone and he's reading about new ideas and then everyone starts listening to him and then they all turn on him. And like, literally, it's just Émile at the end. It's Émile getting people to listen. Even Émile's exact notes of epiphanies he had at the time are directly in the book.

PDR: That's cool. I actually just read a Zola book too.

STC: Really. Which one?

PDR: I can't remember the name in French. It’s The Ladies' Delight in English. It's about the first Parisian department store. It's really cool. And it's, like, funny because the book's like a hundred and forty years old or something.

Random Girl: Hey, do you guys mind if we sit here?

PDR: Yeah, yeah, go for it.

RW: Cool.

PDR: Wait, we should probably move.

STC: Sorry, we're just recording. You're good, you're good.

PDR: What was I saying... Zola. Zola. It's like there are these scenes in the book of a young woman who starts working at this department store and making barely any money. And it alternates between shifts of her at work and then just her spans of time in her, like, decrepit little bedroom. And reading it I'm like, this could literally, like, be my story "Comme".

STC: Yeah, exactly, exactly.

PDR: And I'm not saying that in a vain way. I don't think mine is comparable, but just that that closeness of the novel, or the closeness of fiction to life. And Zola does that really, really well.

STC: And there's such an emotional component that like the book I read definitely has. This man moves to a new town, like needs to work, starts working, has a woman he's interested in, you know, and then like anyway, it gets all like incesty and French and weird, and it was really good. I was just like, damn. But yeah, we were talking about whether everything has to deal with living. I think it has to. Even if you're a person who needs to make a million characters to filter your perspective, it's still saying something about you. Not in a bad way.

PDR: I think it's that thing of everyone's different. But I also think it's not actually about artifice or lack of artifice, autobiographical or not, but it's sort of, I don't know, trying to get to something real really quickly, and that's about what's real for you. If you're going to have this project that's going to take you all of these years to do, it's got to be close to you. You have to be wrestling with something.

STC: Right. I mean, that's honestly, like, so obvious to me. And then I'm over here in interviews being like, "No, it's like not autofiction like, you know, like fuck you" or something like that, you know, or I'm just like or I don't know or like, what is autofiction, what are you talking about? With my book, whether it was happening on a planning level or a more intuitive level, like all the stuff we're saying about like the voice and like toggling like the feeling component and the syntax component, all of it was just based on this, like, nebulous idea of the book's title.

It's funny, like, I went to an Eileen Myles reading and that reading is in the book, but it's not like I was there the whole time being like, "Oh, damn, like, yo, yo." You know, I was there and there was a point where I was like, this is relevant to like the Fuccboi universe. Take that part and like blow it up and like, keep building this tone of being jokey and cheeky.

PDR: I think it's maybe like a weird collapse, especially when people read autofiction they seem to like... I don't want to be too broad. It's not everyone, but I think some people have a hard time delineating the difference between the author and the character.

STC: Right, right, right, right, right.

PDR: And that collapse is partly intentional on the author's part but the relationship is a lot more nuanced. Things can be different. You can play with things. It isn't a direct transcript of yourself or your life.

STC: Oftentimes when I talk to writers, they read kind of how I read, you know, where like you're always aware of how the author is playing. Like in Houellebecq's The Map and the Territory there's Jed the painter who is like a version of Houellebecq's ideas about art or a way of exploring art. But then there's a character called Michel Houellebecq, you know? So he's playing with that. That's what's exciting. So the purpose of titling that is to invite other readers who don't read like that back into why reading can be exciting. It's about the intersection.

PDR: Yeah.

STC: That's partially the idea in Fuccboi. Do I regret it? Nah, I'm just playing. It's too late for all that.

PDR: I think novels can just do something in a weird, exciting way, but also at the same time, as you said before, right, it's been doing this for like hundreds of years. It's like we just call it something different. I don’t know. Maybe we call it a roman-à-clef, maybe we say an autobiographical novel, or like in Fuccboi Sean's mum talks about the Japanese "I" novels. Maybe we call it whatever.

STC: Completely. Sometimes readers are disappointed with it or feel like it's a trick, like, "oh, you're just writing a bunch of real shit.: But there's no real. Everything is a performance. The only thing you can do is have performances of people or characters trying to deal with real stuff. Like, especially what I'm writing now. Like, for a year, some of my experiences were too real to fucking write stupid words about them, you know. And finally, I'm like, oh, I can find pleasure and joy in it again, like, writing.

I've been going to these plays, these Matt Gasda plays, and there's so much more artifice, but then I'm like, but kind of not because as you're writing, you're doing a performance too.

PDR: Yeah, it's a performance. It's a construction.

STC: It's all art, you know? But then, like, there is some striving for something. Like you are kind of striving towards something real. But you get there by fully accepting that there isn't a real that you could fully represent.

PDR: The real always escapes you. You can never get to the real, and when we talk about something real, it isn't like the idea of whether or not something happened, but it's something deeper. People can get really hung up over whether something actually happened and like it could have happened, but it doesn't matter because I'm calling it a novel.

STC: Right, right. Yeah, that's a Rob Doyle bar. A novel is like a series of texts that I decide to call a novel. Nietzsche is similar. About how like everything is appearance. (Truck passes) I wonder how this audio's gonna be dude. It's kind of sick that we're in the world. Be out here in the world.

PDR: I think it's going to be fine. I just hope I can transcribe it. When you're writing, how close do you get to it emotionally as you're writing it?

STC: I was just going to ask you something in that vein. But what do you mean?

PDR: Like, say, like one time I interviewed George Saunders, and I asked whether when he's writing something that feels really sad or really poignant, is he feeling that? Or is he laughing as he writes. I think his answer might have been an evasion, but he's kind of like, no, you know, it's all just work. Personally, I don't feel it that way at all.

STC: Yeah, I don't feel that. Like, I swear to God, only in the past three weeks I feel like I'm actually writing again. I don't know what happened the last six months, but it wasn't writing. It was like fucking dealing with a million things. I've been writing down almost like mantras or declarative statements of what I'm trying to do. With Fuccboi it was a lot more unrestrained. Like, how can I be laughing and crying at the same time? You know what I mean? And with some of those chapters, I would dwell on what I knew the chapter was about, like, planning—I never planned anything before, and that was probably why nothing was ever good—and then I would be hyper-aware of like the moment of inscription. I would get a six-pack and go to this one pizza place. And after the third tall can, I would stop being able to write, but like from one-and-a-half cans to three, I could. I don't want to encourage drinking and I only did that with some chapters, but that's how I got to some of that, where I'd be like fucking bawling, like giggling and bawling.

PDR: Yeah.

STC: But I don't know if that's how I'm going in now. It's different. I think before I might have had faith in the most emotional urgent thing having inherent value. And I still think there is some of that, but I've also been noticing events and situations recurring. Like something happens in a similar way in my life, and I'm trying to figure out what really happened before. Was that good or bad? Are you going to do the same thing over again? And like, I'm writing about an old event or a bunch of events, but I'm actually thinking actively about what's happening currently. That's really made the writing come alive again.

PDR: Yeah. You're reaching an emotional immediacy but in a different way. I get that.

STC: Last night I tried to drink to write again. That's why my face is all inflamed. I can't be drinking. I got some like rice sake I thought would be good because my face gets red as soon as I drink beer.

I wrote for 2 hours, and then, like, this song came on and I just started bawling. I cried for like an hour. And then I was really tired, and I went to sleep. I thought this is such a waste of drinking, but it's also like, maybe that was the day's writing.

PDR: I don't know. Sometimes it can be important to get to an emotional point or to understand something, even if that's not the time that you actually write it, because it helps you write it later. And that doesn't have to be through alcohol. It's just emotionally dealing with it.

STC: Yeah, completely. Getting into that state. But you know, earlier when I wasn't able to write, I was still like writing, but I would feel like I had to write from that place, and that was too painful. Looking back on it, it was too painful. That's why I was like, remembering, like, the playful element and that you're not always going to be able to get to that intensity all the time. I think you kind of have to be in a good place, you know. You should be feeling things, but you can't be like, fucking wrecked all the time, you know. You need to guide the work. You're making something. You're guiding a reader.

Where do you fall on that question? Say in like the first story from your collection. Do you feel like you write more urgent from intimate sharing? Or do you feel like it's different now having had a book come out?

PDR: I don't know. I think I'm always trying to deal with something that's from a very real place. So, like, my life wasn't, you know, anything like the character's in "The Hard Thing". But emotionally, I was often in this place where I just felt I was in a kind of freefall. I was often feeling manic. I was sort of doing things, and then afterwards being like, why did I do that? Or you'd be in the moment of doing something and be like, "What are you doing Paul? Take it easy." And really that's what that story is about. Sometimes it can be overwhelming, like going again and again to maybe a darker place. But I also think there's this thing which is like, I have a lot of fun with my stories. They're funny, and that isn't incidental.

STC: Yeah. I think I try to do that too. Like I'm not going to write two-hundred pages just like beating you with pain and hurt. But like when it turns to that, after a quick stack, then goes back to doing something else, it's like a little zap telling the reader to wake up.

PDR: Yeah and it's like, I don't know what the new thing is going to be, but it's going to be different in that it's going to be a novel. So I think that's just inherently different. You've got that space and you have to use it. So emotionally it will be interesting. But I also don't want to be sad all the time. I'm similar. I want to be playful.

STC: Yeah. Have you read Ben Lerner?

PDR: Yeah.

STC: Have you read 10:04?

PDR: Yeah.

STC: I hadn't read any Ben Lerner until Sheila Heti told me to read his first book, but I read his first book and then I've been dipping my head into his second. There's a part where he goes on a residency.

PDR: Yeah, the Marfa one.

STC: He's just, like, on a bender, like all nocturnal. That was reminding me of your MacDowell experience. But then, earlier, I wanted to bring it up because we were talking about artifice versus the real. That's so much a part of the book. Like he writes about Donald Judd then sees the Judd works. And I really just stopped at that part last night.

PDR: Has he gone to the party yet?

STC: He's about to. He's about to. He's like, I've been alone for three weeks. All right, I'll hang out with people. And then he's just going to be like wilding out.

PDR: There's this incredible line I love. I'm paraphrasing, "I was going to go home and like work on my novel, but I knew I should be going home to work on the novel. And then I was in the car going to the party." Or it's something like that.

"I said I should probably go home and work on my novel, but never intended to, and soon the four of us were driving through the dark to the party." (Ben Lerner, 10:04)

STC: Oh, I got to show you! That's literally where I'm at in the fucking book. Look at this. He just did his Donald Judd rant. He's writing the fucking book. That's so wild. But that's also a thing I go through constantly too, when someone's like, come to a thing, and I'm like, no, I gotta write. And then, as soon as I say that I fucking can't write anymore. I'm just like, oh, so what am I doing just sitting in this cave?

PDR: Yeah, I get that completely. Well, like even at the residency, I was pretty social. You'd be like seeing everyone every night at dinner and maybe drinking and maybe playing pool. But for the most part you'd be isolated, just alone, like writing in your cabin. Sometimes I'd notice myself getting frustrated with being like, why aren't these words coming to me? Why have I run out of steam? And then as soon as I was on the Amtrak, I was out in the world, like laughing at something someone did at the station, I was writing. I was writing a lot.

STC: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. You have to be connected to life. You can't only learn to write at the library. You know, like, you have to be out here fucking feeling things and fucking navigating relationships. That's what I'm always saying. Participate in the world.

*