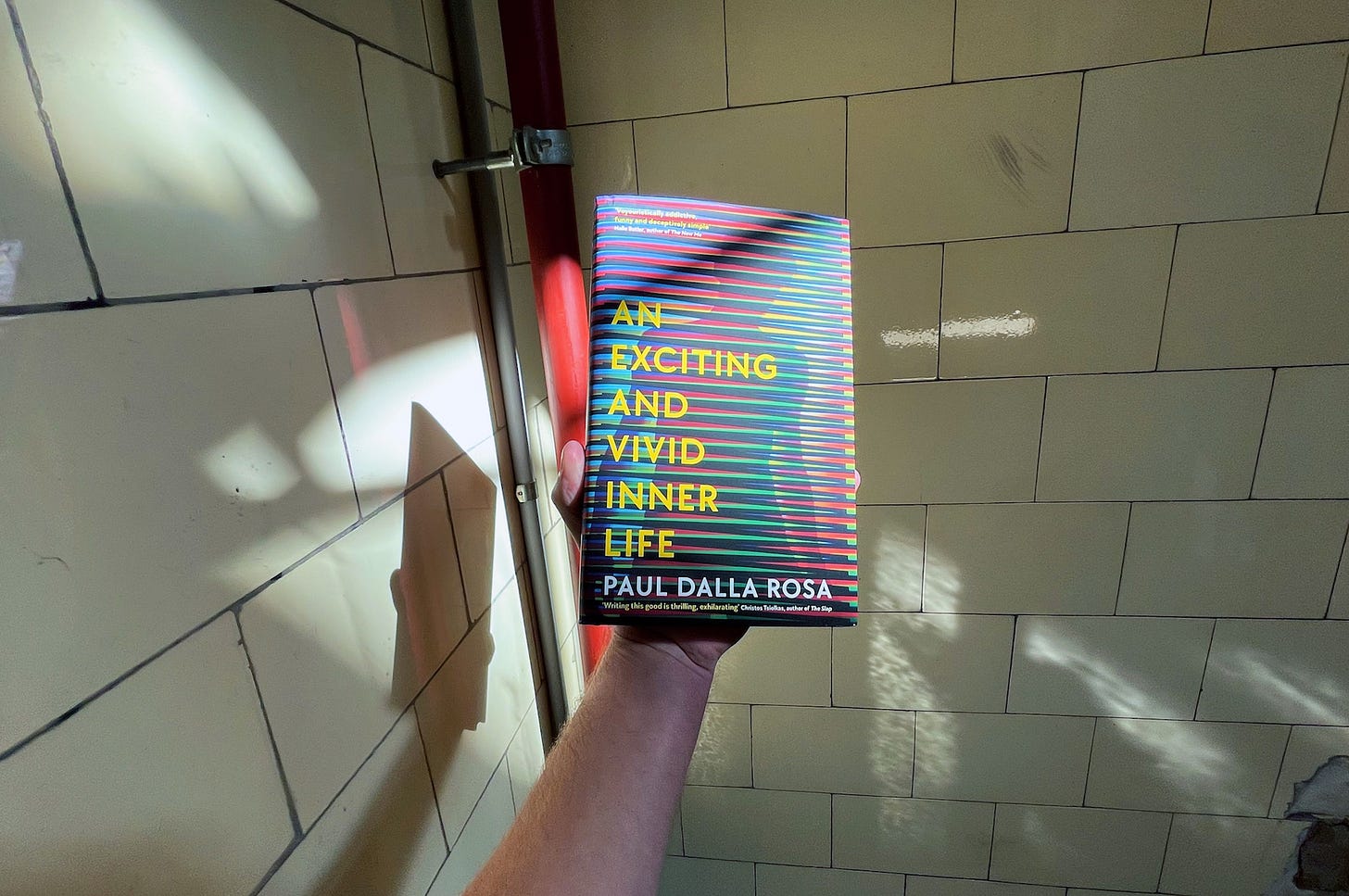

Bad Artist Statement #8: Paul Dalla Rosa

Emma and I talk about story collections, An Exciting and Vivid Inner Life, writing the virtual, and visualising yourself as a sim.

This Bad Artist Statement is a little different. For the release of my debut story collection, An Exciting and Vivid Inner Life, Emma Marie Jones offered to have a conversation with me as the subject. As I wrote introducing Bad Artist Statement #2, "Emma and I have been close friends for years, at certain points having crises of individuation."

We spoke about the book, which follows a series of millennials who often do dumb, sometimes outrageous things attempting to leap over the gap between their aspirations and their reality. They send emails they shouldn't send, use credit cards they should cut in half, and sometimes take photos of themselves in the positions of animals, the position of a dog.

Emma and I talk about story collections, An Exciting and Vivid Inner Life, writing the virtual, and visualising yourself as a Sim.

Emma Marie Jones: I can hear feedback. I can hear my own voice.

Paul Dalla Rosa: Oh, hmmm. Can you still hear it now?

EMJ: No. Well, I wasn't speaking, but I'm not hearing it now.

PDR: Okay, good. I think it's because I'm, like, talking into my laptop. Maybe. Whatever. Do you want to lead?

EMJ: Yeah. I have a list, but it's very out of order and incoherent. I sort of just wrote things as I was reading the collection.

PDR: Incoherent is good, I think.

EMJ: This is my first time reading all of your stories together and reading more than one of them in a row. I liked it. It all worked together in a way some collections don't. You're a more dedicated reader of short story collections than I am. I tend to start reading them and get like halfway through and then, sort of like hyperactively, jump from that book to another book, like a novel. I think I'll come back to the stories and finish them, but then I just never do.

PDR: I think collections can be hard to read.

EMJ: It's more of an effort for me to stay focused on reading all of the stories in a collection in order than it is for me to read a novel.

PDR: Well, I think that's why, you know, I really purposefully made the collection slim, and I really was ready to fight on the collection's length. I was lucky I didn't have to. I think what can be challenging with a story collection is that the reader has to do so much work because each short story is a new story with new characters, a new situation. If the opening of a story isn't perfect or doesn't flow, the reading experience becomes dissonant, whereas it's very easy to sit down and read a novel because you don't have to do that work every time you open it. You can just kind of float in and out.

EMJ: I hate to do the Moshfegh comparison, which is like mandatory for every like new young writer to be touted as the next Moshfegh. Like it says it on your book jacket. But I think your collection and her collection share something, which is like a really tight thematic link or a shared voice that makes it feel like less work to go from one story to the next story. It's very easy to move from one to the next, like a well-curated mix.

PDR: Yeah, Homesick for Another World has that quality. I also think of Jen George's The Babysitter at Rest. Those collections are really, really tight. That's what I wanted for An Exciting and Vivid Inner Life. Sometimes I really hate when a short story collection is just like, here is every random short story that I wrote in this large period of time. Unless it's like someone's collected works or that person is naturally obsessive over something.

EMJ: Yeah. It has to be more deliberate. I had a short story collection that I did love. April Ayers Lawson's.

PDR: Oh, yeah. Virgin and Other Stories. I liked that collection.

EMJ: That had a very different quality from your stories. It's more of a gothic, like, languorous feeling. But it was the same thing where it was like moving between the stories felt pretty easy.

PDR: I think it's hard to achieve. That's what I hope my book achieves. I really tried to think about what makes a short story collection a collection. And there's a tendency where people think for publishing that to do a short story collection it has to be an interrelated short story collection. That was the fashion for a while, but maybe it seems less the case now. But I think that's almost like a misidentification or too literal an interpretation. It's like, oh, it must be cohesive if the same characters appear throughout it. Some collections that do that are really great, perfect collections, but in my opinion, a short story collection should be linked enough, whether on a stylistic or emotional level, without necessarily having to use that as a conceit. To me, it should be a literary work with the same kind of resonance as a novel.

EMJ: Yeah.

PDR: Anyway, that's me ranting about stories.

EMJ: No, I think that's good. I think that's why I sometimes find writing short stories quite easy—to write a story, it's just a self-contained little thing. But I feel like even if I just think about the various short stories that I've ever written or started writing, I couldn't even begin to think about how to write them or like present them together in a way that didn't feel really disjointed.

PDR: Well, you said a mix before and that sounds right to me. To me, a collection should be like an album. Like , I don't know, in every Lana Del Rey album each song is different, but they do have a connecting, unifying concept that comes together. When I was writing the collection, especially when I reached maybe the midpoint, I was thinking of it almost like a musical fugue. Something's introduced in one story, then complicated in another, then refracted. I was thinking about that a lot.

EMJ: Yeah, a consistent throughline.

PDR: I often think of a Lana quote that she gave in an interview, and sometimes it's bad when I do this because usually I kind of paraphrase or have the risk of completely inventing them, but someone asked, Why did you choose the name Lana Del Rey? And she said she chose the name because she wanted a guiding star for her work, as like something or a concept she was moving towards. And I think a short story collection or any work of art should do the same.

EMJ: Yeah, with its title or just with its kind of mood.

PDR: Not with its title necessarily, but just that idea of moving or having some kind of compass. That doesn't mean you can't do a lot of different things. It just means that those things aren't completely random but that you're reaching towards something.

EMJ: It's interesting to talk about movement. I have it written in my notes. I don't know what you think, but I feel like reading the stories from your book all give me this sense of being stationary. There's a standout scene that exemplifies that feeling, which is when in "I Feel It", all of the guys are on a yacht, but they're not going anywhere.

PDR: Yeah. It's moored.

EMJ: And it's kind of like, I don't know if all of your characters are like this, but there's this desire to move or progress, but that isn't really happening, and everything's kind of stuck in the mud.

PDR: Yeah, and in certain ways most of the movement that occurs is like between the stories. So, you know, you have a shift to a kind of completely different vantage point, sometimes of the same emotional problem or an extension of that problem. But when the characters themselves are in it or the stories, they often, yeah, they are stuck. They're sort of mired in their situation and can't always move out of it.

EMJ: And, I mean, the title kind of suggests that you're keeping that in your mind when you read the stories. But I feel like the video of the javelina running in "Contact" is the emblem of the actual movement, which is happening in a fantasy space or just like a private space.

PDR: I can see that. The characters might be stuck in their situations and there is a constant attempt of trying to be free, but because they're stuck the movement or action often occurs or is sublimated into an imaginary.

EMJ: Yeah, and the javelina video, I feel like it's just a perfect metaphor for so many of your characters because it's like this aimless or directionless movement, just like random movement. Just as long as it's still moving, you know?

PDR: Yeah, and the fact that the movement repeats itself, like a GIF or a video stuck on autoplay.

EMJ: Yeah. It's what Lauren Berlant would call an impasse, this loop of being stuck in a fantasy.

PDR: Yeah. An impasse sounds right to me. I also think with what you brought up with movement... If I'm going to intellectualise it. It's sort of like, I think the moments in the book that are really just… I don't want to say transcendent exactly—

EMJ: I think that's the right word.

PDR: It's a little grandiose, maybe, but yeah, these moments where that lack of movement or that kind of oppressive atmosphere or impasse opens up for an instant. And that is almost like, you know, a shift in a piece of music, a choral arrangement at the outro of a Kanye song or something like that, something that soars. And to do that really does take a lot of work at the level of the sentence, but to me, those really are moments of freedom within the book, however momentary they might be.

EMJ: I really see myself a lot in those characters, or I can relate to very specific things they experience in the stories, but it's like you use the word transcendent. It's quite beautiful to see that even in these situations which feel inescapable in the moment, there are these breakthrough moments that might be so fleeting or so temporary, but that this beauty can, like, visit you even in the most sort of sedentary situations of your life.

PDR: I think that's when beauty is most likely to hit you, and I think the stories wouldn't work or, more so, the collection as a whole wouldn't work without them. They're vital to the book.

EMJ: I feel like those moments of insight are like a PDR signature. I feel like you are really good at articulating those moments both in your writing, but also when we've been having like drunk rants at each other or just talking on the phone. You can identify these little transcendent moments of something higher in something that feels like a trap.

I feel like I know your characters really well because I read your stories through different stages of the process. I feel like I've come to know, especially some of the characters, extremely well. How do you feel about your characters now that they're, I guess, no longer yours?

PDR: I guess my relation to them is weird now. Estranged. I do think when I write there's an almost method acting quality, like inhabiting the character, getting emotionally very close. Now I'm further away from them, but sometimes… I'm just thinking how to phrase it. You know, every character in the book isn't me, but at the same time, sometimes I can look at the stories and it's like watching a scene from Being John Malkovich, and every character is me. Or that moment in Chelsea Hodson's essay collection that describes the island of Chelseas. Thankfully, that only lasts for like a second at a time.

It's interesting seeing other people's reactions now that it's out in the world, and some of those reactions can be close to disgust or like really hating the characters or how horrible they are, which to an extent, I get. Still, I personally don't really make moral judgements on them. It's not really my place as the author, and I truly do feel a lot of affection for them. At my weaker moments, while writing, especially dealing with some of the younger characters, I'd feel guilty like I was taking a character, putting them in a walled room in The Sims and then lighting a fire and deleting the door. At the same time, none of the characters are real. They're just these textual signifiers.

EMJ: I think they're more than textual signifiers to the author.

PDR: You're right. That was a deflection.

EMJ: I mean people I've heard a lot of like really corny like famous author interviews like where people say that their characters are like their children to them. And it's like, I don't think that's a very good analogy, but I think your characters are all of you.

PDR: Well, like, you have a child, and I think you can clearly see that a character and your child are not the same at all. I think "of me" makes the most sense. Every thought that a character has, I've had to have that thought while I write it.

EMJ: Exactly. I feel very affectionate towards them too. I think they're very well realised, very relatable. As you say, they might not be the most like moral kind of teachers or like exemplars for us or whatever, but I think that that provides a little space for this sympathy and affection, sort of like, oh, you fucked up.

PDR: Yeah, the characters might be selfish, or they might do questionable things, but I think a part of that comes from paying attention to people and knowing that people are all fallible. And, you know, the characters I write really are irradiated by the society that surrounds them. We all are.

EMJ: And I think, yeah, if the characters did the quote-unquote right thing every time they were presented with a choice, I don't think the stories would be terribly interesting.

PDR: I would find them boring, but I find most things boring.

EMJ: One other thing I wanted to raise, which could lead us somewhere that we'll go for two minutes or maybe two hours, is talking about digital representations of characters and creating that from a craft perspective as well. I'm really interested in talking to you about the ways that you negotiated online spaces in the stories and with your characters. I feel like there are two really good examples. Sam kind of toggles himself to third-person view in "Short Stack", and in "Charlie in High Definition", Emma views herself as a rendering on a screen. The characters see themselves as digital versions of themselves, but you also present text messages, Grindr, etc. as almost background noise.

PDR: Yeah, I think it's throughout.

EMJ: It's not like making a point out of it. It's kind of just there.

PDR: Well, I think it's something I think about a lot because it can be very uncomfortable and almost cringe to show online things because the things we use online are constantly changing, and those changes are actually accelerating, so they date very quickly. Sometimes you read a novel or story that does it particularly poorly. It's like you can intuit something about it doesn't work.

EMJ: That's my biggest fear with my writing. It's that I'll navigate depicting sending a text message or a transcript of an MSN chat and that it will be really cringe in a few years to look at the way that it looks.

PDR: I actually think the novel you're working on does it really well, and also your novel is a period piece, so I think that strengthens it too. It's connected to the internet at a very specific time.

EMJ: You know angelicism01?

PDR: Yes. I wish I could say I'm not as online as I am, but yes.

EMJ: I saw them using slashes to separate text messages in a write up of a text message conversation. Almost like how you would indicate the line break of a poem without doing a line break. And I thought this is cool. Maybe I should play with this. And then I tried it by writing a couple of lines of our text message conversation with slashes between them and it didn't work. It made us sound like pretentious fucks.

PDR: Maybe for what they're doing, you know, this attempt of an almost like avant-garde digital stream of consciousness, it works. I can see it. Though I don't really know what's going on there.

EMJ: Yeah, and the messages I used was just like us talking about, I don't know, like, whatever, some television show we're watching which is like hardly profound.

PDR: It's just different. I would say I read with great interest certain writers who I think depict online reality well. Say, what Tao Lin's been doing for over a decade is bringing digital communication into literature in a very direct, almost unmediated way. I think Megan Boyle does that really, really well in Liveblog. Lucy Ives' Cosmogony has, I think, the best description of a meme I've read so far. I like what Honor Levy is doing. All of that is exciting to me.

EMJ: Good. I was going to mention Liveblog. Liveblog shows the present really well.

PDR: It's almost impossible to show contemporary life without the internet and digital communication being involved. So you need to have a way of representing them. And I also think there's a thing which is just that I do believe that consciousness is becoming more virtual and being online is actually changing us beneath the threshold of our consciousness. It's reformatting us. This isn't a novel idea, Byung-Chul Han and Bifo write a lot about it, but it's one that's really fascinating to me. I also think we live more and more in a reality where our physical spaces are turning more virtual or hollowed out to resemble the virtual. It's flattening. That feeling like everywhere's an airport. At the same time, the sense of the self begins to more and more fracture into the idea of yourself as an avatar that can constantly be edited, curated and refracted.

EMJ: Yeah. But I think it can also do this weird thing that you show in your stories, which I can't really decide if it's good or bad. For instance, with Sam in "Short Stack", when he's like fantasising about if the pancake saloon was in Grand Theft Auto as a playable destination or whatever, it's like, it's not really a good thing or a bad thing, it's kind of just a thing. And I think The Sims can do that to you too. If it's like, say, I'm like waking up at 4:00 in the morning to feed the baby and then I have to like wash up a ton of bottles and then go back to bed. It's like I almost am looking at it as though I'm going to click on the sink and choose "wash bottle", and then I'm going to click on the bed and choose "go to sleep". And it feels like it makes what I'm doing less banal somehow.

PDR: Well, it's an imaginary.

EMJ: Exactly, it's like I can sort of make this feel less shit than it is by imagining that it's a game.

PDR: I think so. I really like something Gary Indiana writes in Vile Days that one of the roles of artistic development or artistic movements isn’t “…to negate the value of what preceded it, but to keep the recording of consciousness up to date.” And I think, often what I'm showing, I don't really have a value judgement on a lot of this stuff. We exist in hyperreality. To me that's just an objective statement. There are certain things that I really despise about virtualisation and engagement metrics and dataism. To an extent, I really do hate those things. I revile them. And you know, I have a bad habit of when I'm drunk just ranting about like, I don't know, Boolean logic like I'm doing my own angelicism01 screed. But I try not to do that in the stories themselves because I think I'm more interested in depicting what life is as I'm seeing it. Though maybe my critique's still there if you read between the lines.

EMJ: Yeah. So you and I love to whenever we come across one of those things on Twitter that's like, using four images from your camera roll show what it would be like to date you or show what items you would drop if you were killed in a video game or whatever. And we always send the images to each other rather than tweet them. I wanted us each to do an image that to us describes reading the collection in some way.

PDR: Let's do it.

EMJ: I'll do mine first. I hope you won't feel insulted that I've got a meme.

PDR: I'm all for a meme.

EMJ: Okay, I'll just text it.

PDR: Okay. I like this one.

EMJ: I feel like this one is self-explanatory. I feel like you already know which stories it applies to.

PDR: Yeah. Which stories would you apply it to?

EMJ: Well, I feel like you could also easily apply it to… God. I'm like, actually looking at the contents page and thinking, like, basically, like, all of them.

PDR: Yeah, I would agree with that. I like it. I like the image because there's this, you know, fantasy aspiration aspect to it. What is that in the background? Like a palace?

EMJ: Actually, I have no idea. It's like one of those deep-fried memes. But like anything you might have to complain about your own circumstances is like you're a customer but you're also the manager.

PDR: Yeah. This could actually be like a bad Byung-Chul Han meme. He writes about this in The Burnout Society that we're no longer in a disciplinary society but an achievement society that has internalised the workman and foreman in one. You're your own manager. You're your own brand. It also kind of reflects something I really hate about the current bureaucratisation of everything. Like all of our emotions that are very normal, all of our interactions and discontent have to be channeled through this management process, almost all like HR-ification of the soul.

EMJ: Yeah. Everything is now in a rubric of experience and feeling.

PDR: Do you want to say anything else about it?

EMJ: I feel it's pretty self-explanatory.

PDR: Okay, I'm sending mine.

EMJ: Oh I recognise this. It's from that book that has the documentary—Generation Wealth.

PDR: Yeah, by Lauren Greenfield. I always feel guilty about this book because I remember when I bought it, you really wanted it and you'd wanted it for ages, and we'd talked about you wanting it for ages and then I bought it for myself and didn't want to tell you. One day you came over and I actually hid it.

EMJ: One day I'll buy it. I'll probably never buy it.

PDR: It really is this beautiful object of depravity.

EMJ: It's a great looking book.

PDR: I was watching the documentary and rereading the book last week and it struck me that a lot of the locations in the book almost match up one-to-one to the places Greenfield did assignments in: Dubai, Iceland, China, Los Angeles. It's interesting how that happened because I really don't think I had the book in mind. I think when I was writing the book, I was following capital in a similar way she was.

EMJ: Yeah, but from a different angle. Maybe.

PDR: What do you think of the image?

EMJ: It looks like a really shit party. That's the first thing that comes to mind.

PDR: Definitely. I love this image because it's like, you know, so many characters in the book have this desire for, you know, bottle service or to be a part of this sort of image of wealth, which is also obscene. Luxury, wealth, and excess in almost all instances, relies on the subjugation of someone else. This photo, well, a lot of her photos, capture it perfectly. So in this image, certain characters might desire this life, but most likely they'd probably be the woman who's on her hands and knees, a piece of furniture. Actually, no, in most cases, they probably wouldn't even make it into the club.

EMJ: Yeah. It looks like something that one of your characters would like cut out and stick on a mood board for their own life.

PDR: They would and they'd misidentify themselves in it.

EMJ: Okay, I know we said one, but I just want to send one more. The image I'm sending is very small because it's actually a really high-res image and my phone can't deal with it.

PDR: Perfect Blue.

EMJ: Yes. Do you remember when it's from in the movie?

PDR: No.

EMJ: Okay, I'll explain it because it explains why I picked it. It's from right at the end, and I don't want to spoil the movie for anyone, so I won't go into the detail. But essentially, what she's saying at the moment of this still is something like, I'm the real one, or, It's really me. And it's kind of like this moment that could be ambiguously read as two identities collapsing into one another in either one direction or the other.

PDR: Oh yeah. It's like the end of Safe when Julianne Moore says 'I love you' to her reflection. God, I love this film. The fashion show scene. Just Mima on her Mac. And how do you see that with the book?

EMJ: I think because many of your characters are sort of teetering on the edge of such a collapse where there are multiple versions of the self and in many of the stories, there's a choice of like which way is the character going to take this? Which one is the real one?

PDR: Yeah, It's ambiguous which way they're going to go. Perfect Blue has a really interesting thing in that it's about, in part, the terror of the internet but also this subject with multiple selves or shadow selves, having to collapse them together into a person or accepting all facets of that person. The two seem connected but inverted. The internet seems disastrous to the self. The other thing I love about it is that it really shows that the blurring of fantasy and reality becomes untenable at a certain point.

It's funny, when I started writing the book, I had a still from Perfect Blue on the wall above my desk.

EMJ: Which one?

PDR: It's like her in her little Tokyo apartment talking to her agent. So the plot is that this woman who is part of a successful J-pop group decides that she wants to leave that career where she was very comfortable and become an actress. It's not quite working out for her, or it's more difficult than she expected. And this still was on my wall before any of the stories from the collection were published. I don't think we knew each other then, or maybe just in passing. I was eating a can of tuna and brown rice a day and feeling psychologically wretched. I was coming off a lot of pain medication which probably wasn't helping. But, anyway, I'd look up at this still while writing and it had this subtitle at the bottom which was a message for me rather than any comment on the stories.

EMJ: What did it say?

PDR: "It's hard, but I chose to do it."

*